FENCING...

...is a combat sport between two individuals, each armed with a similar weapon and takes place in a strictly defined playing area. There are rules governing such things as the validity of the target and the way in which points or "hits" may be scored. The modern sport uses three weapons (foil, epee and sabre) each with its own distinct rules and characteristics. Please click the buttons below for details of each weapon.

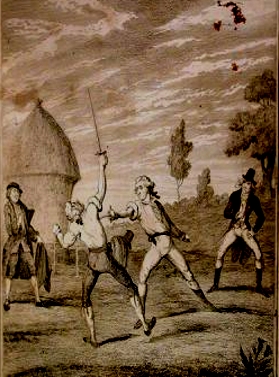

Origins

Modern sport fencing is assumed to have developed from the duelling tradition prevalent in Europe from about the late 16th to the end of the 19th Cs. There is confusion as to its actual origins; some saying it was developed in its own right as a game or pastime, others saying that it developed from exercises used in preparation for actual combat. It may be that both are true, as of the two weapons most commonly fought, epee and foil, epee very much has the character of a "duel made safe" where almost anything goes provided the point lands. The restraints and limitations of foil, however, seem to recreate the training exercises of the classroom, emphasising the need for defence and the delivery of a killing stroke.

Epee

The modern derivative of the Duelling Sword is the Epee. This has a tapering blade no more than 90cm long and triangular in cross section mounted eccentrically on a large, almost hemispherical guard behind which there is a handle whereby the fencer holds and manipulates the weapon. The whole thing must be no more than 110cm long and weigh no more than 770g. Several characteristics of the Epee point to its origin as a combat weapon:-

The conventions of Epee also mirror the "first blood" convention of the formal duel. The whole body from the toe to the head and from the shoulder to the hand is valid target and, unlike foil, there is no convention of "right of way"; if both fencers are hit simultaneously, then a point is scored against each of them. Indeed, in its origin, Epee contests would be fought for one hit and the fencer receiving the hit would be deemed to have "lost" rather than his opponent having "won". This is the case today in special "One Hit" Epee competitions where, if both fencers are hit, then each suffers a defeat (is fencing the only sport where both participants can lose?).

Foil

In contrast to epee, foil is often seen as an overly complicated weapon, very difficult to understand, especially for non-fencers, with rules or "conventions" governing, the placement, target and validity of the hit. But if we remember that that Foil was developed from a need to practice the killing art in a safe manner but that in itself it was never a killing weapon, then all the conventions that cause problems for the would-be Zorros and D'Artagnans "because it wouldn't be like that in a proper fight" make sense.

The basic conventions in Foil can be summed up as "Point", "Target" and "Priority". Click the buttons below for a more detailed discussion of each.

Point

The most basic convention in Foil is that it is a "point" weapon; that is, only hits scored with the point can be counted. Slashing or cutting actions are not allowed.

Further, in order to score, hits must be "material" hits; that is, they must have the "character of penetration" (what this means is that if the swords were sharp they would stick in). Before the invention of the electric scoring system, when matches were judged, "by eye" a material hit was one which caused the weapon to bend. Nowadays, a pressure switch resisitant to a pressure of 500g is mounted at the tip of the weapon. Apparently 500g was determined to be the amount of force required to drive a sharp point 5cm/2ins into flesh. Deep enough to reach the vital organs of even the most corpulant of duelists!

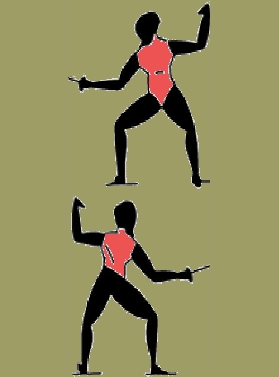

Valid Target

The valid target area is limited to the torso as this is the area of most damage. Although the convention was to fight to first blood, this was by no means always the case and the best way to survive (short of not being there in the first place!) is to kill or incapacitate your adversary as soon as possible. This is best done by running him through the torso, as a blade through the vital organs is likely to prove a great deterrent to further belligerence. In contrast, a hit to the wrist, although satisfying the honour of the situation, may only serve to infuriate your adversary and lead him to redouble his efforts to kill you.

"Off Target"

As well as the valid target area, foil also recognises an invalid or "off target" area (head, arms, legs etc) and while hits in this area don't usually score, they are acknowledged and the action stopped. This is another point of confusion for the non-foilist; why stop the "flow" of the fight if no point has been scored? However, if we again look back to the origins of fencing, we can see that, although a hit in the off target area is not a killing stroke, it is a stopping stroke. In a formal duel, if either party was injured, the fight would be stopped to allow the wound to be dressed, the principals would be asked if they had come to their senses and in all probability, the matter would end there. However, as we have said, foil fencing was designed to train the killing stroke, so although the action is stopped for a "wound" (i.e. hit off target) this is not the object of the game and so no point is scored.

Right of Way or Priority

In foil, if both fencers are hit, it's the Referee's job to determine the "Priority" and to award the hit accordingly. Again, this harks back to the idea of training to kill without yourself being killed "accidentally". The Rules say that if a fencer is attacked, then s/he must defend themselves ('parry') BEFORE they are allowed to strike back ('riposte'), as the attacking fencer has "right of way" (or "Priority") in the attack.

Consider a Tennis match. If Player 'A' is in the middle of his service (attack), then Player 'B' must wait and then attempt to return it (parry-riposte) to score a point. He can't simply whip out another ball and try to "serve" first. Similarly, Player 'A' must wait for the ball to be returned; he can't just serve another ball right after the first. As the ball passes backward and forward between the tennis players, so Priority passes from one fencer to another.

Sabre

Sabre differs from the other two weapons in that hits can be scored with the edge of the blade as well as the point. In its original form, only the front edge and the top third of the back edge would count, hits with the sides and lower two thirds of the back being considered "flat". This was to mimic the construction of Cavalry sabres, which were sharpened along these edges to make their use from a charging horse more effective. As the sport moved further away from its martial origins and became faster and more athletic, so it became more difficult to differentiate between valid and flat hits so, pragmatically, the rules were changed to allow hits with any part of the blade. Indeed, with the introduction of electrical scoring apparatus, it was impossible to design practical equipment that could make the differentiation between valid and flat hits.

Sabre Conventions

Like foil sabre grew out of the need for safe practice and so it, too, has conventions. Like foil and for the same reasons, sabre has right of way and a limited target area. The valid target is that part of the body above the crease of the hip including the arms and the head. Traditionally this is said to be that area that was vulnerable without risking the horse upon which your opponent sat, but this is rather a romantic fancy. The reason the legs are " off target" again comes down to the idea of the "killing stroke". If you are fighting an opponent on horseback, there is little point attacking his legs. In the heat of battle, it is likely that quite severe injuries to the legs would be unnoticed under the rush of adrenaline. Attacks to the torso or head could, of course deliver fatal injuries while cutting attacks with the heavy blade of a cavalry sabre to the arms could result in amputation or at the least severe damage leaving your opponent unable to wield his sword or control his horse. In either case, he would be a sitting target for your next attack.

What does it take to be a fencer?

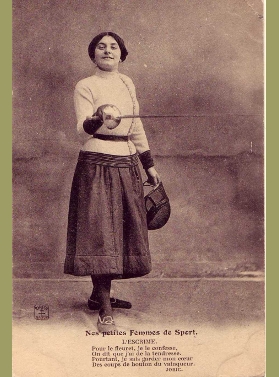

In the first instance, it takes a willingness to learn and a little application. To learn to be a good fencer also takes a sense of distance, a sense of timing and to some extent a degree of co-ordination, although it has been shown that fencing can help develop these skills where there has been little evident before. Note that there was no mention of strength. Unlike other martial arts (judo, karate, boxing etc.) fencing is not concerned with weight categories and although in official competition, the sexes are mostly segregated, in the club situation, men and women often fence together. Neither is physical disability a barrier to fencing, indeed it is one of the more popular events in the Paralympic Games and there are several fencing clubs that integrate ambulatory and wheelchair bound fencers very successfully. Deafness is certainly no barrier to fencing and it is possible for the blind and partially sighted to participate also.

Fencing can be enjoyed whatever your age; a simplified form can be introduced to children as young as seven an I personally have fenced a very competent 80-year old sabreur who did not start fencing until he was 70! All in all, whether you want to experience the grace of ballet, the tactics of chess or the romance of the three musketeers, you will find it in fencing.